The whole thing came crashing down because of an informant. And not just any informant — a “well known harlot.”

Hispala Faecenia, the harlot in question, was a freed slave woman who worked as a prostitute in the Roman Republic. When her lover, Publius Aebutius, told her that he would have to spend some time away from her for religious reasons, she pressed him on his intentions. He said that he was preparing for the Bacchic rites. The historian Livy tells us that

When the woman heard this, she, perturbed, exclaimed, “Good gods!” She expressed that it would be better for him and for her to die rather than to do it, and she called down threats and perils on the heads of those who had advised it.

Hispala, it turned out, had spent some time around the cult of Bacchus in her previous life as a slave. She warned him that the rituals there started with “the pleasures of wine and feast” but became immoral, dark, and disturbing, saying that

There, no wickedness, no shameful act was left untried. There were more lustful acts among men with one another than among women. If any of them were less inclined to suffer abuse or reluctant to commit the crime they were sacrificed as victims. To consider nothing as a crime was the highest religion among them. Men, as if with their minds seized, fanatically tossing their bodies, told prophecies; matrons in the dress of Bacchantes, with loose hair and carrying burning torches, ran down to the Tiber, and plunging their torches in the water, because their torches contained live sulfur mixed with calcium, they brought them out, flames still burning. The men were said to be snatched by the gods, whom bound to machines were carried out of sight into secret caves: they were those who refused to either swear an oath or to join in the crimes or to suffer shame.

The cult was especially popular among nobles, who liked to initiate children into their rituals. Hispala said that the cult took in “no one more than twenty years old.”

Publius took her advice; instead of joining, he went to the consul and told him everything. This led to an investigation by the Senate, which found that Bacchic gatherings went beyond debauchery — they represented something even more disturbing.

The Bacchic rights, the investigators found, weren’t just a frenzied sexual free-for-all; they were a danger to the Roman state. People were being murdered, their cries muffled by the ecstatic drumming and singing of the cult members. Investigators feared that the priests of Bacchus were orchestrating the murders, eliminating politicians they didn’t like.

So the Roman government arrested the cultists, putting some of them “in chains” and executing “those who had violated themselves by debauchery or murder, who had polluted themselves by false testimony, forged seals, substitution of wills or other frauds.” The cult of Bacchus was no more.

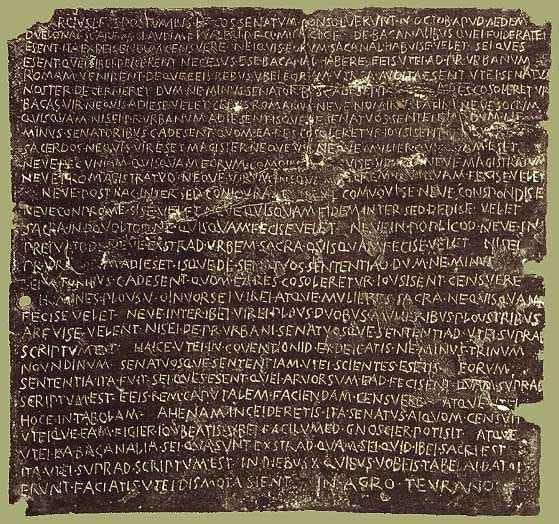

Maybe this is how it went. But probably not. There was a cult of Bacchus in Rome, and it was outlawed, or at least seriously conscribed. We have the Roman Senate’s decree on the matter from 186 BCE (it’s actually the oldest Senate decree ever found), which stated that no one could join the cult without the permission of the Senate:

But Livy’s account, which I quoted above, was written two centuries after these events. Most historians think his version of events is exaggerated and moralistic. As Ingo Gildenhard puts it, Livy’s is

a vivid and salacious chronicle of the affair, in which sex, intrigue, and xenophobia register insistently. It is, in fact, shot through with Augustan anachronisms; whether consciously or not, Livy has inflected his treatment with contemporary concerns (such as Augustus’ moral legislation).

The cult of Bacchus, a god of wine who sometimes went by the name Dionysius in Greece, was real, and so was its reputation for wildness and excess. It was already old by the time of that Senate decree — it shows up in Euripides’ play The Bacchae, which was written 200 years before the decree and 400 years before Livy wrote about it.

Euripides’ play has some elements that rhyme with Livy’s account. There are mysterious rituals kept secret from the uninitiated. Gallons of wine are consumed amidst riotous music and dancing, all of which whips revelers into an altered state. And there’s terrifying violence — at one point, the maenads, the female followers of Dionysius, tear animals and even a man apart with their bare hands. The moment was immortalized in a painting in Pompeii:

Whatever the truth of the ancient Bacchanalia — most historians accept that they did happen, but weren’t as salacious or sinister as some ancient sources contend — its story didn’t end there. The cult of Bacchus had a second life in the early modern period, where it came to represent an entirely new set of ideas.

The bronze tablet with the Senate’s decree restricting Bacchanalia was found in 1640 in Tirolo, Italy, but by then the cult of Bacchus was already back — in art, at least.

As Renaissance scholars and artists revived knowledge of the ancient world, they came across the stories of the Bacchanalia and were no doubt fascinated. Imagine being a devout Christian exiting the relatively dour Middle Ages and coming across these stories of frenzied, wine-soaked orgies. You’d want to paint them, right?

One of the earliest artists to depict a Bacchanal was Andrea Mantegna, an Italian printmaker who produced this image in 1475, likely based on an ancient sarcophagus. It’s focused more on the drunkenness than the sex of the Bacchic rites:

Titian was one of the first major painters to try his hand at the genre, in his “Bacchus and Ariadne,” painted in the 1520s. Bacchus here leads a parade of revelers:

He followed up with “The Bacchanal of the Andrians,” showing the rites on an island where the rivers were said to flow with wine. The paper in the bottom center of the image has a little ditty on it with the lyrics, “Who drinks and does not drink again does not know what drinking is.”

Why did artists like Titian choose the Bacchanalia as a subject? There are practical reasons — it gave them an opportunity to depict people in all different stages of frolicking, and the nature of the Bacchic rites allowed them to try their hand at nude figures. Classical subject matter afforded them an excuse to portray much more sensual scenes than they normally would, and this was the most sensual of all classical subjects.

Baroque artists loved the Bacchanalia, too. In the early 1600s, Peter Paul Rubens celebrated the sheer fleshiness of the whole thing. The people here are meant to represent the “over-ripe” fruit that’s harvested just before winter, one last bit of excessive pleasure before the harder times of winter:

Meanwhile, Nicolas Poussin created a much more restrained version of the events, more closely mimicking classical inspirations:

Although this Poussin Bacchanal is a little more sensual:

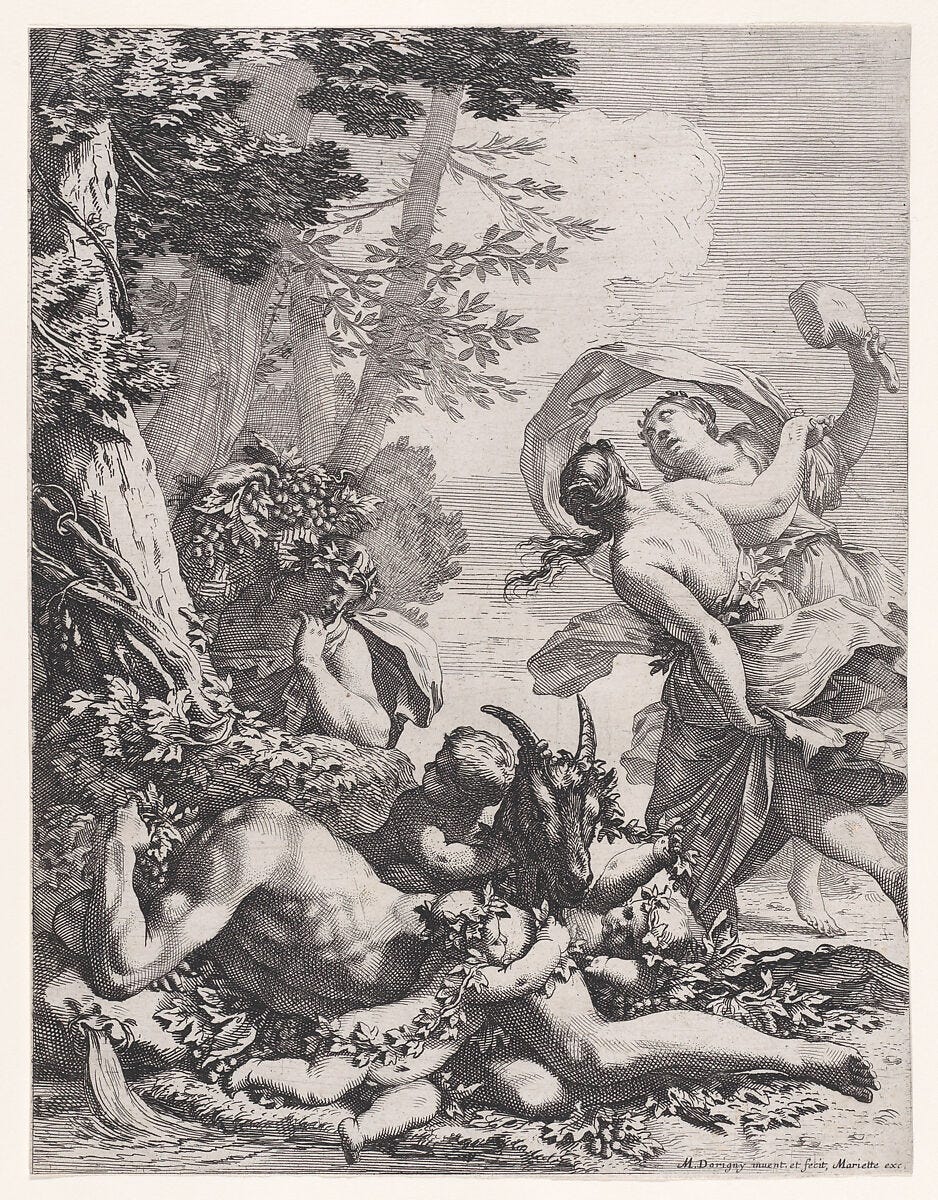

Michel Dorigny, too, created a more sober version of the rites in the 1630s:

This bowl (which might be a 19th-century forgery, but might be from the 1500s) juxtaposes John the Baptist in the center with a Bacchanalia marching around the outside:

Hey, have you noticed all of the weird babies in some of these paintings?

These chubby little guys are putti: cherubs who, by the 1600s, variously represented heaven, love, or leisure. Sometimes painters would just throw them into works to fill up the blank space. Their cheerful visages fill up many of the more innocent varieties of the Bacchanalian scene. Sometimes they’re the only characters, as in this German medallion:

Or this Otto van Even painting from around 1600:

By the 1700s, the varieties of Bacchanalia had proliferated. There were neoclassical versions:

Pastoral, Romantic ones:

And giddy, carnal romps:

In the nineteenth century, artists added an element of realism to their depictions of Bacchanalia. Lovis Corinth painted these revelers staggering home after a long night:

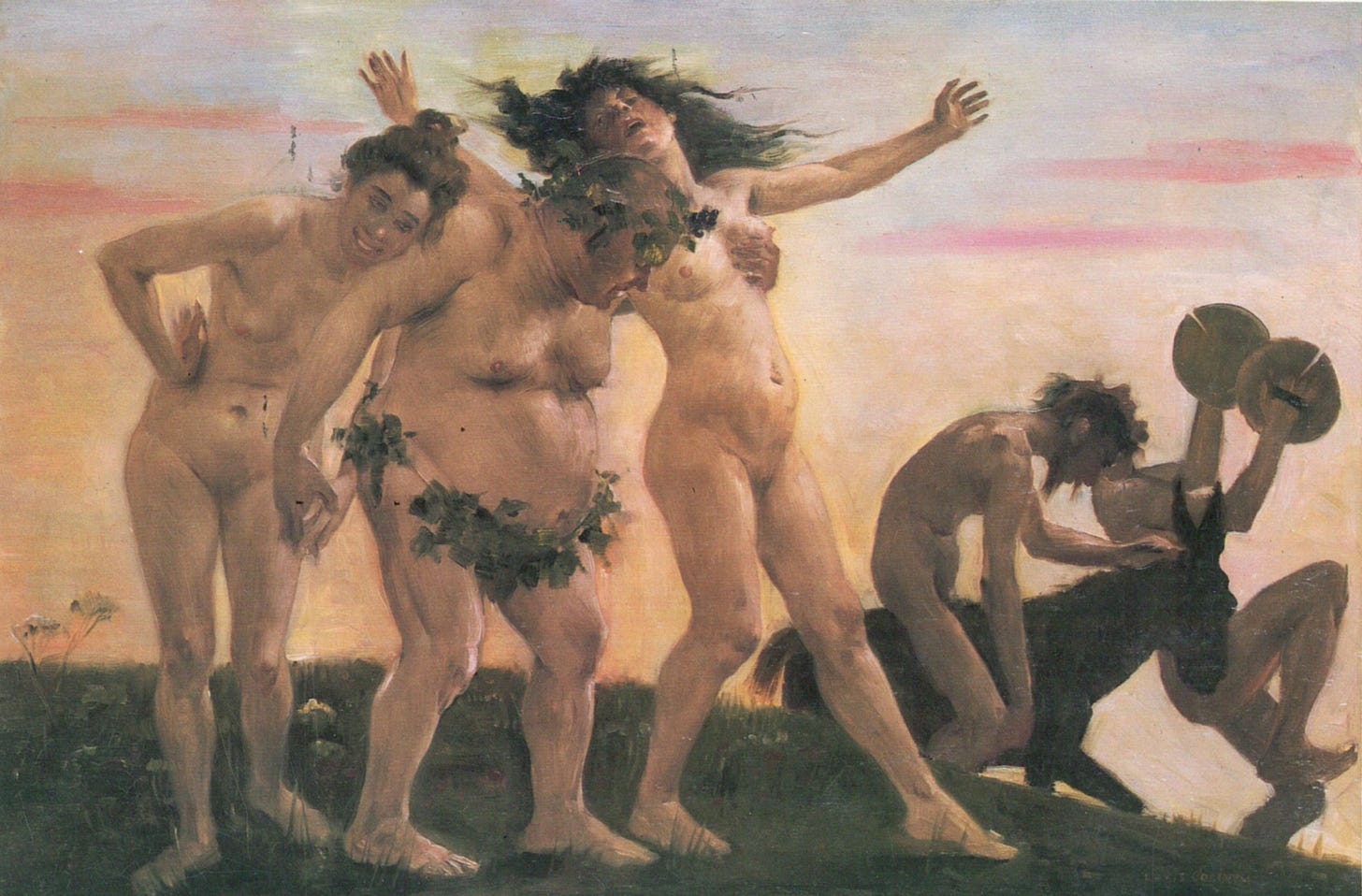

While Auguste Leveque painted a more wanton, confused scene:

The fascination with Bacchanalia continued into the twentieth century. Pablo Picasso was an especially big fan, but his artwork’s copyrights are tightly controlled, so you’ll have to click through to see some examples.

What were the Bacchanalia really like? Were they the stately frolics of Nicolas Poussin, the boozy romps of Peter Paul Rubens, or the wild orgies of Auguste Leveque? Were they the murderous, secretive cults that Livy describes, or just misunderstood religious practices?

It’s hard to tell, although it’s not difficult to understand why people have been drawn to them for so many years. Bacchanalia allowed artists to explore the tension between order and chaos, the pursuit of pleasure, and the loosening of inhibitions. Some artists found these ideas inviting; others found them dangerous. And a few probably just appreciated the excuse to paint a bunch of naked people.

This newsletter is free to all, but I count on the kindness of readers to keep it going. If you enjoyed reading this week’s edition, there are three ways to support my work:

You can subscribe as a free or paying member:

You can share the newsletter with others:

You can “buy me a coffee” by sending me a one-time or recurring payment:

Thanks for reading, and I’ll see you again next week!