The United States Constitution has been through all sorts of difficult tests in its two and a quarter centuries. It weathered the Nullification Crisis, in which South Carolina refused to comply with federal tariffs; the Civil War, which tore the country apart and killed 600,000 Americans; and the elections of 1824 and 1876, when the Electoral College failed to deliver a clear winner and winners were chosen through “corrupt bargains.” And future historians will, hopefully, think of the last decade as another set of crises that the Constitution has survived.

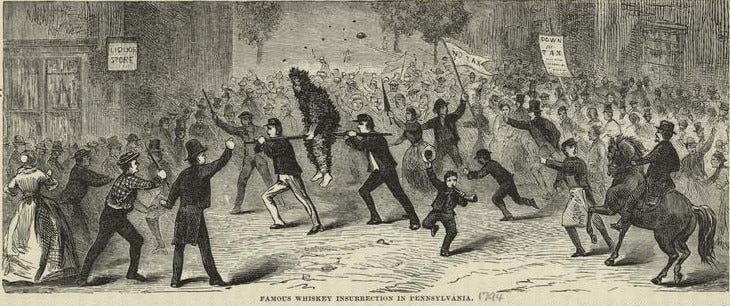

The very first test of the Constitution came when the document’s ink was barely dry. In 1794, hundreds of armed insurrectionists in Pennsylvania tarred and feathered tax collectors and burned down a government official’s house.

In response, George Washington ordered thousands of militiamen to march against the rebels. The rebellion quickly crumbled, but it was an important moment in American history. It turned out to be one of the first rounds in our eternal national debate over how strong the federal government should be. In this case, federalists like Alexander Hamilton won out over anti-federalists like Thomas Jefferson.

What made Pennsylvanian farmers angry enough that they were willing to rise up in an insurrection? The government was coming after their whiskey.

This weird illustration, dating to 1791, shows what Americans were willing to do to protect the whiskey trade — on the right, a tax collector has seized some barrels of whiskey from farmers; on the left, the farmers are hanging him — and blowing up a keg of whiskey underneath him for good measure (and, well, in the middle, an odd little monster hooks him like a fish. I didn’t say it was a realistic depiction of events).

The Whiskey Rebellion of 1794 was an early salvo in the battle over how powerful the federal government should be, but that’s not why I want to talk about it today. That short-lived insurrection also showed how important alcoholic beverages were to American culture and economics.

When we think about the history of alcohol in America, we tend to focus on Prohibition, which was, to be sure, a fascinating moment in American history. But Prohibition didn’t come out of nowhere.

So this week, we’re going to look back further. Since our founding, Americans have been a nation deeply conflicted about alcohol — many of us consume the stuff in immense quantities, but there’s always been an uneasiness about the role that alcohol plays in American life.

The first thing to know is that early America was awash in alcohol. Even the Puritans, abstemious about so many things, drank all the time and considered alcohol to be a gift from God. In fact, the Mayflower only ended up in Massachusetts because the ship was running out of beer. The sailors, who had to make a return trip across the Atlantic, worried that they might run out of suds before they got back. So they dumped their passengers at Plymouth Rock instead of their preferred destination, the Hudson River. The ship’s crew had to wait until spring to make the return voyage, so they sat offshore, enjoying their beer but refusing to share, all winter.

As Bruce Bustard writes, the Puritans weren’t alone. Alcohol was a big part of life everywhere in early America:

Men, women, and even children swallowed “a healthful dram” with breakfast. Farmers took cider, beer, or whiskey into their fields. Employers gave their workers a mid-morning break for an invigorating swig. Ale accompanied supper, and a “nightcap” was typical before bed. And while drunkenness was seen as disruptive to community, social occasions such as weddings, barn raising, elections, christenings, and funerals were opportunities to indulge.

Even though some of the alcoholic beverages they drank weren’t as strong as they are today, early Americans drank a lot of alcohol:

In 1790, we consumed an average of 5.8 gallons of absolute alcohol annually for each drinking-age individual. By 1830, that figure rose to 7.1 gallons! Today, in contrast, Americans consume about 2.3 gallons of absolute alcohol in a year.

There were two reasons for the prevalence of alcohol in early America. First, plain water was often unsafe to drink, and people distrusted it (this was especially true on ships like the Mayflower, where the water would stagnate and fester for weeks on end). But it was also true that life for most people was pretty boring, and the work they did was repetitive and painful. Alcohol made life easier and provided calories to boot.

But from the very beginning, Americans had a love-hate relationship with alcohol. Increase Mather called alcohol a “good creature of God,” but his son Cotton feared that a “flood of RUM” might “overwhelm all good Order among us.” Rum seemed to be a particular problem — King George II singled it out when he banned certain beverages in Georgia in 1733:

Whereas it is found by Experience that the use of Liquors called Rum and Brandy, in the Province of Georgia are more particularly hurtful and pernicious to Man's Body and have been attended with dangerous Maladies and fatal distempers… NO Rum or Brandy nor any other kind of Spirits or Strong Waters by whatsoever name they are or may be distinguished… shall be imported or brought to shore.

George Washington was one of Virginia’s most important whiskey makers. He won elections and kept his troops happy by giving out alcohol liberally. But he also understood its drawbacks. This letter, to Thomas Green, a carpenter at Mount Vernon, lays out Washington’s thinking about the danger of drinking:

The sure means to avoid this evil is—first to refrain from drink which is the source of all evil—and the ruin of half the workmen in this Country… Were you to look back, and had the means, either from recollection, or accounts to ascertain the cost of the liquor you have expended it would astonish you… But the expence is not the worst consequence that attends it for it naturally leads a man into the company of those who encourage dissipation and idleness by which he is led to by degrees to the perpetration of acts which may terminate in his Ruin—but supposing this not to happen a disordered frame—and a body debilitated, renders him unfit (even if his mind was disposed to discharge the duties of his station with honor to himself or fidility to his employer) from the execution of it. an aching head and trimbling limbs which are the inevitable effects of drinking disincline the hands from work hence begins sloth and that Lestessness which end in idleness—but which are no reasons for withholding that labour for which money is paid.

Washington wasn’t the only founder to have suspicions about alcohol. Benjamin Franklin wrote,

Drunkenness is a very unfortunate Vice in this respect. It bears no kind of Similitude with any sort of Virtue, from which it might possibly borrow a Name; and is therefore reduc’d to the wretched Necessity of being express’d by distant round-about Phrases, and of perpetually varying those Phrases, as often as they come to be well understood to signify plainly that a Man is drunk….

He published the “Drinker’s Dictionary” in 1737, listing all of the euphemisms one might use for drunkenness, organized by letter. Here’s how it starts:

A

He is Addled,

He’s casting up his Accounts,

He’s Afflicted,

He’s in his Airs.

B

He’s Biggy,

Bewitch’d,

Block and Block,

Boozy,

Bowz’d,

Been at Barbadoes,

Piss’d in the Brook,

Drunk as a Wheel-Barrow,

Burdock’d,

Buskey,

Buzzey,

Has Stole a Manchet out of the Brewer’s Basket,

His Head is full of Bees…

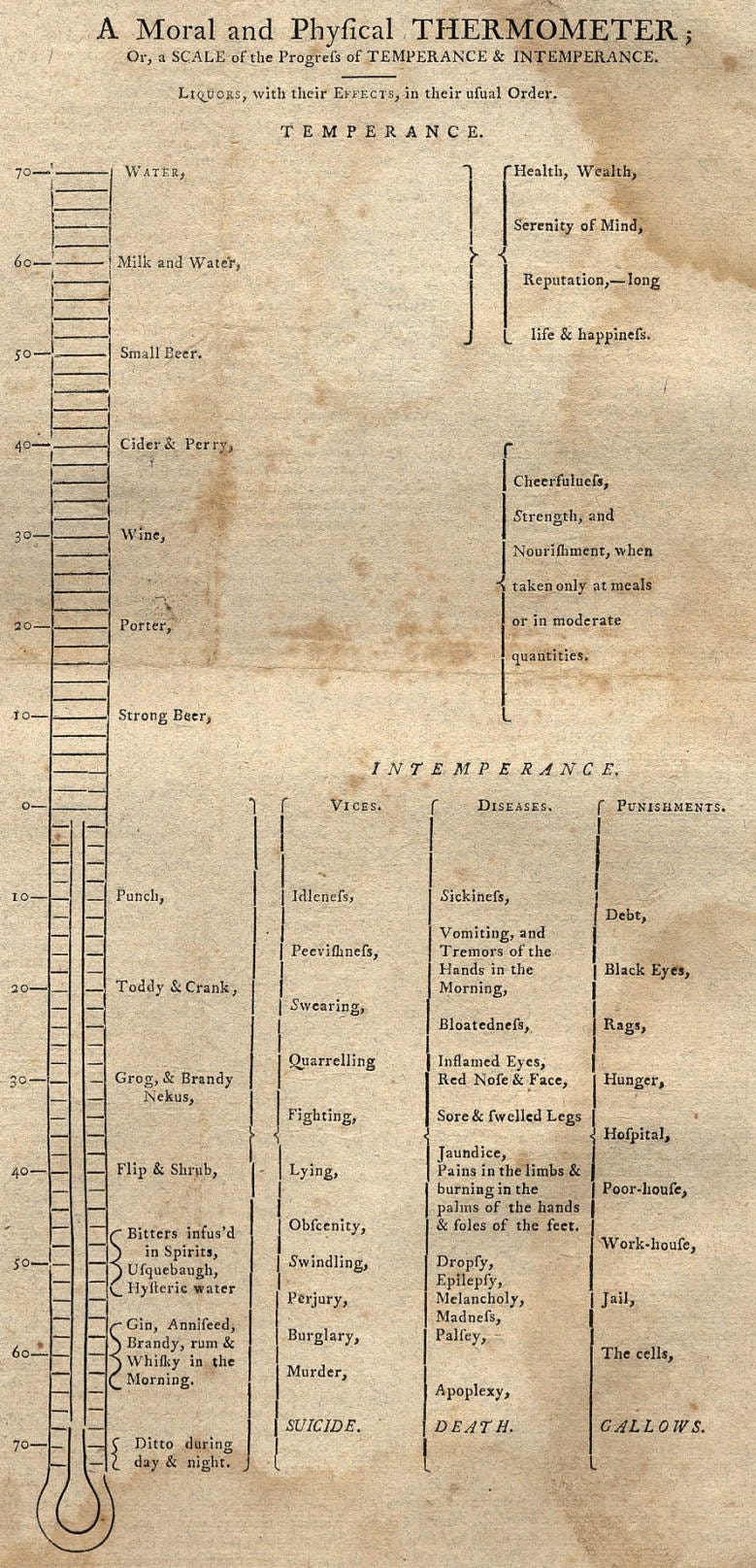

Benjamin Rush, a Philadelphia physician who signed the Declaration of Independence, became one of the early champions of what would later be called the temperance movement. In 1785, he wrote an essay called “An Inquiry Into the Effects of Ardent Spirits Upon the Human Body and Mind,” which included a “thermometer” to measure the effects of various beverages. As you can see below, water and milk bring health, wealth, and serenity. Cider and wine induce cheerfulness and strength, while the hard stuff — much of which is delightfully named: toddy, crank, grog, flip, shrub, hysteric water, etc. — can cause anything from idleness to epilepsy to “SUICIDE,” “DEATH,” and the “GALLOWS.”

John Chapman was born just before the American Revolution in Massachusetts, but he seems to have been lured west from an early age. At 18, he took his 11-year-old half-brother across the Appalachian frontier to live a nomadic lifestyle. Chapman devoted much of his life to spreading a single crop across the American heartland. Because he was responsible for planting countless apple trees in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, and other states — sometimes just scattering seeds wherever he walked — he entered American folklore as Johnny Appleseed.

Unlike Paul Bunyan and other subjects of American tall tales, Johnny Appleseed was a real person who had a real impact on the growing country. Apples did not exist in the New World before people like Chapman planted them. When I learned his story as a kid, I assumed the apples he planted were for eating — but it seems that they were for drinking. He was planting varieties of apples that would only be useful for fermenting.

Apple cider was the alcoholic beverage of choice for early Americans. Easy to produce and free of bacteria due to its alcohol content, it became synonymous with frontier living and farming. This painting by William Sydney Mount depicts the various steps involved in cider-making, showing them as part of an idyllic pastoral scene.

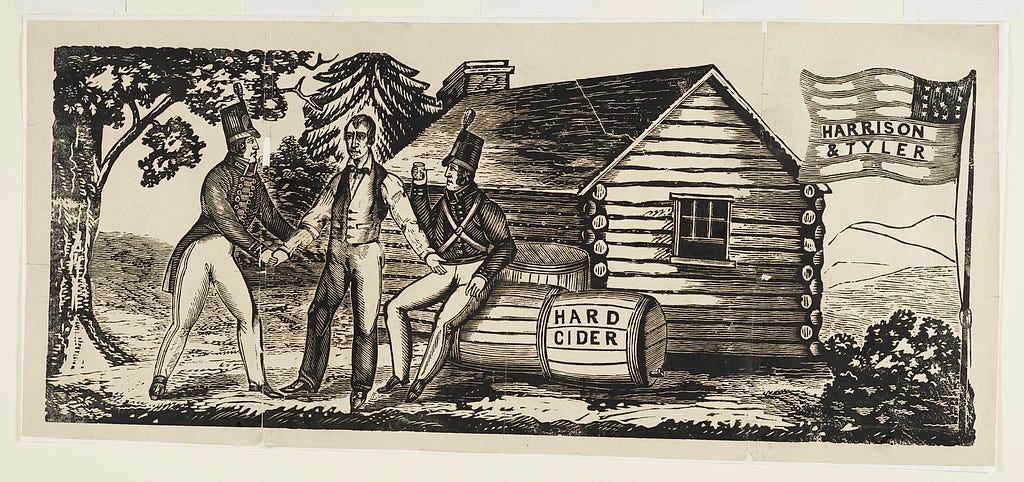

Mount may have made this image as a bit of political commentary. The 1840 presidential election was all about hard cider. The Democrats attacked the Whig candidate, William Henry Harrison, for being an old and simple frontiersman. Harrison leaned into the depiction, presenting himself as a humble farmer who preferred log cabins and hard cider to fancy Washington life (this was a bit of political spin — he really lived in a very nice mansion).

Soon, publications were full of images of Harrison tapping barrels of hard cider:

Hard cider marked Harrison as a man of the people, in contrast to the aloof Martin Van Buren. Harrison won the election quite easily.

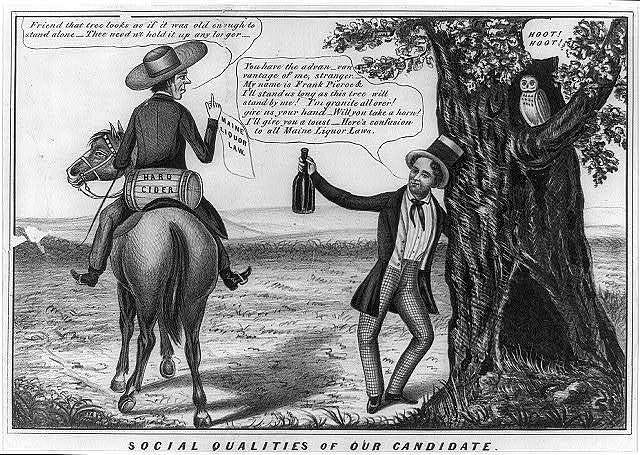

Associations with alcohol weren’t good for every presidential candidate. Franklin Pierce was a notorious drunk, and was mocked as such in this 1852 cartoon. In the illustration, a Quaker from Maine — which by this point had passed a state prohibition of alcohol — tells Pierce: “That tree looks as if it was old enough to stand alone--Thee needn't hold it up any longer." Pierce responds by toasting him. By the way — notice the barrel of hard cider on the Quaker’s horse? It’s probably a reference to the Whigs’ campaign of 1840, and perhaps a hint that Maine prohibitionists weren’t on the up-and-up.

By the middle of the 1800s, as we have seen, there was plenty of discourse about alcohol. Most Americans drank heavily, but these habits worried people who feared that a country awash in alcohol would be morally and economically weak. A temperance movement sprang up, pushing for laws like the one in Maine. In the 1830s, anti-alcohol activists formed the “Cold Water Army,” in which they recruited children to take a pledge to abstain from alcohol:

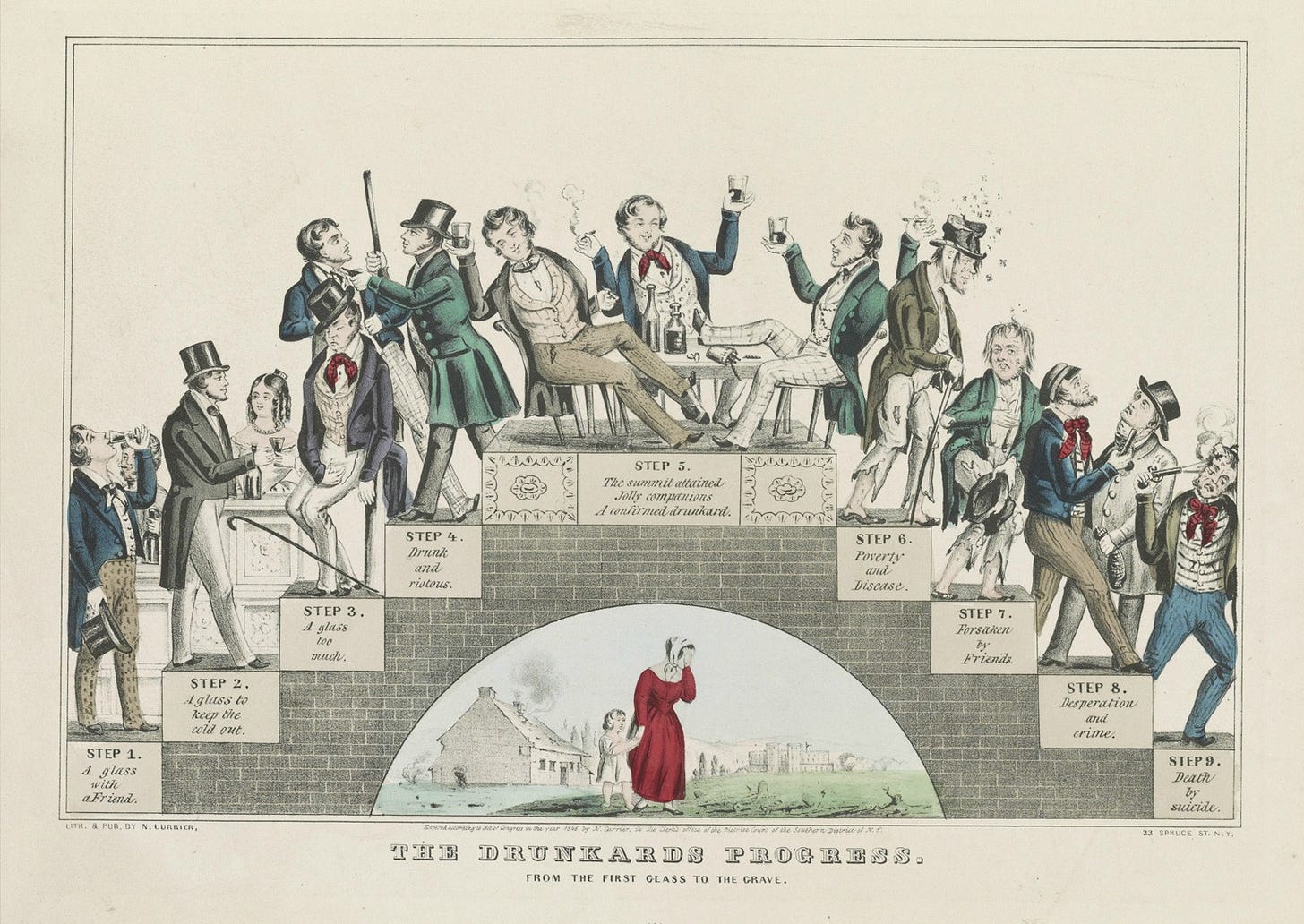

Temperance activists used a number of clever concepts to persuade their fellow Americans to give up drink. Nathaniel Currier published “The Drunkard’s Progress” in 1846, in which the road to ruin begins with “a glass with a friend” and ends with crime, suicide, and a bereft family:

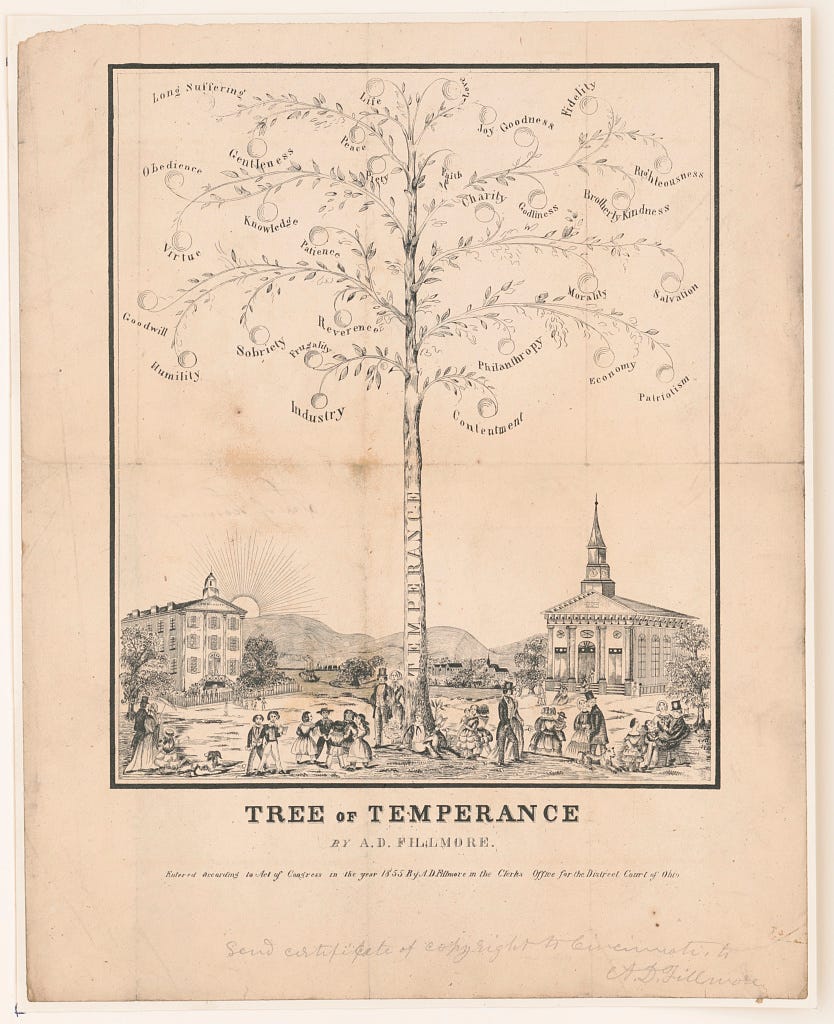

Others used botanical imagery. This 1855 “tree of temperance” bore fruit like contentment, industry, and morality:

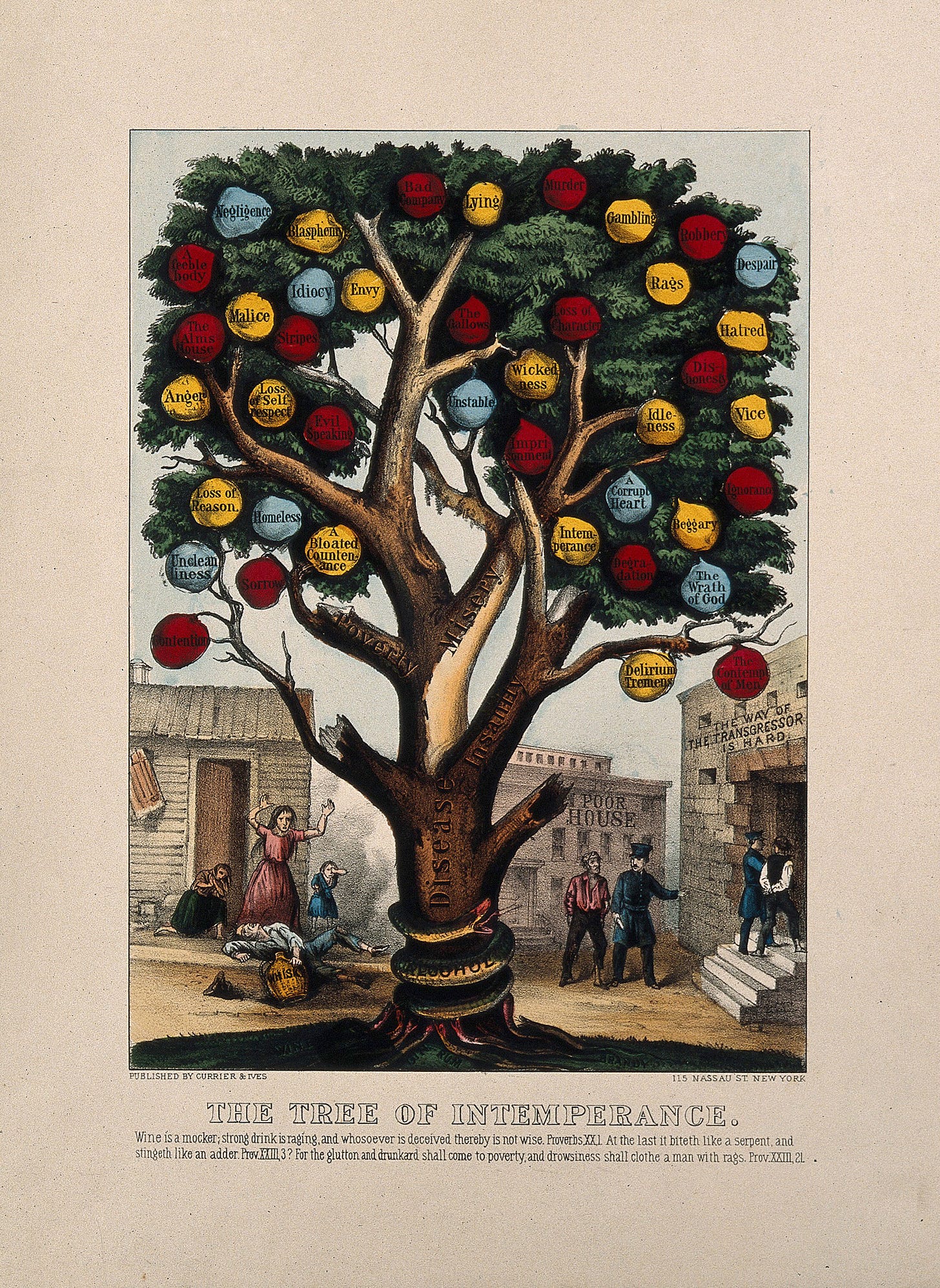

While the tree of intemperance offers up arson, famine, incontinence, and more. A devilish serpent encircles the tree with an apple in its mouth and a crown of beer on its head.

Currier & Ives made a prettier version of these trees a few years later:

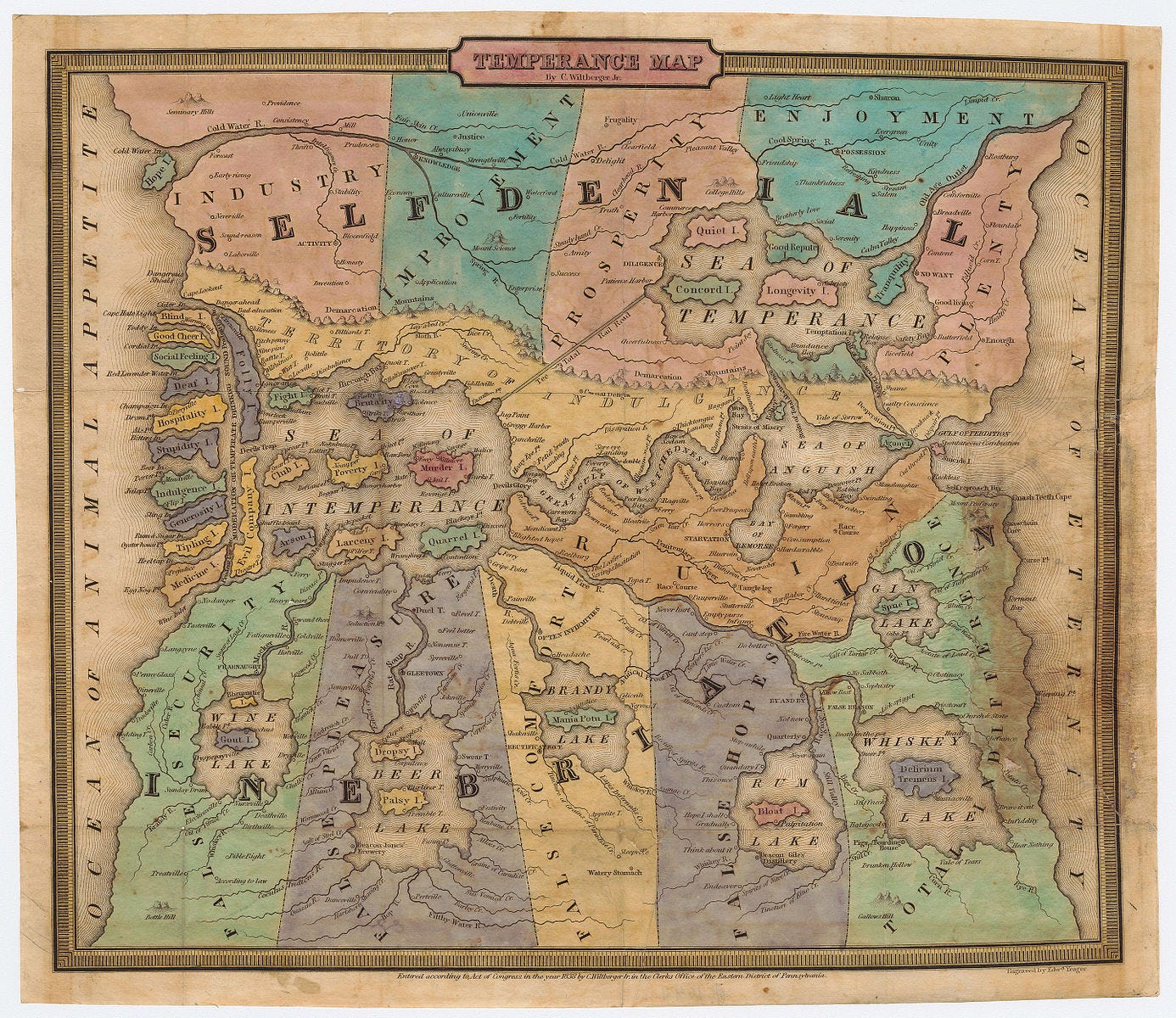

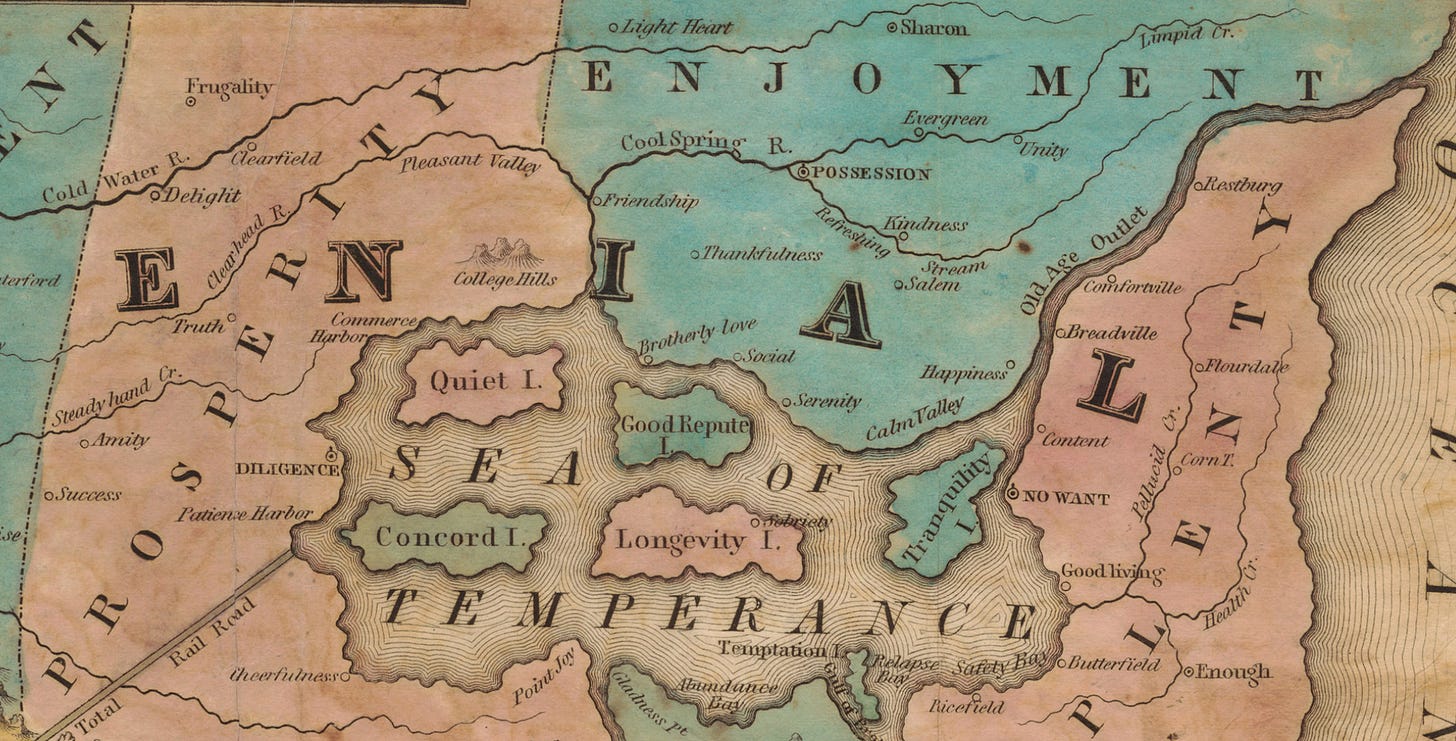

Perhaps my favorite visual representation of the effects of alcohol is this map by John Wiltberger, published in 1838.

The lands of “Inebriation” feature landmarks like the Penitentiary River and Gloom Point, which looks out over the Sea of Anguish:

Meanwhile, take a trip on the Tee-Total Railroad into the lands of “Self-Denial,” and you will reach Friendship and Serenity. And who knows — you might find yourself in the College Hills!

I also quite like this 1871 anti-alcohol “ad” for the “Dead River” railroad, which stops at Sneakville, Cursington, Thieves Gully, Murderer’s Gulch, and Delirium Falls.

By the time the fake railroad ad above was posted, the American debate over alcohol was growing in volume and vociferousness. The temperance movement was gaining steam — by 1850, half of Americans didn’t drink at all, and many states had passed prohibitions on selling alcohol. This movement would eventually result in Prohibition: a great victory for anti-alcohol forces that the country almost immediately came to regret. Americans’ relationship with alcohol would remain complicated.

This newsletter is free to all, but I count on the kindness of readers to keep it going. If you enjoyed reading this week’s edition, there are three ways to support my work:

You can subscribe as a free or paying member:

You can share the newsletter with others:

You can “buy me a coffee” by sending me a one-time or recurring payment:

Thanks for reading, and I’ll see you again next week!

"Once ... in the wilds of Afghanistan, I lost my corkscrew, and we were forced to live on nothing but food and water for days." WC Fields

Loved this! I knew about 19th century temperance, but not the earlier movements, or the role in politics. And as usual, such great illustrations.