I’m on vacation this week, so I thought I would republish this piece from a couple of years ago that I liked but didn’t get a whole lot of traction. See you next week with a new post!

At the very end of the book, his case made, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle delivers a closing statement in defense of a certain William Hope: “He stands before the world as a man who has been very cruelly maligned, and the victim of a plot which has been quite extraordinary in its ramifications.”

Like his most famous creation, Sherlock Holmes, Doyle had assembled in this 1922 manifesto a significant pile of evidence in favor of his case. He had sifted through scientific data, solicited testimony from dozens of witnesses, and dismissed every possible argument against his theory. He concludes with a thundering summation:

Every reader with an open mind will agree that the evidence for the reality of psychic photography is overwhelming. It is only necessary to repeat that these reports form but part of a tremendous mass of accumulated evidence, which is available for any serious student to investigate.

That’s right, in 1923, the creator of the world’s most brilliantly rational detective stuck his neck out in public on behalf of psychic photography (also known as spirit photography)— the belief that cameras could capture ghosts on film.

Doyle, you see, had long been an enthusiast for the paranormal. In the 1890s, between writing The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes and The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes, he joined the Society for Psychical Research and spent some time hunting for poltergeists in the English countryside. By the time the First World War rolled around, he had joined the spiritualist movement, whose promises that one could contact spirits beyond the grave gave people great solace in a time of terrible loss.

Doyle’s book, The Case for Spirit Photography, actually came toward the tail end of the ghost photography craze. It turns out that attempts to capture ghosts on film are almost as old as photography itself.

When it was invented in the middle of the 1800s, photography became an important tool for grieving people.

Today, when we lose someone, we celebrate them, in large part, through photographs. We play a slideshow at the funeral home or pore quietly through old photo albums. Photography gives us a record of our lives, even when they’re over.

When photography was invented, people almost immediately recognized its potential to keep memories alive beyond the grave. It became common in Victorian England, for example, for people to take pictures of their recently deceased loved ones. These post-mortem photos were often the first and last photos taken of children who passed at a young age.

But what about people who were already dead? Could they be photographed?

In 1861, a Boston photographer named William Mumler took a self-portrait. When he did so, he mistakenly used a plate that had already been exposed. The result was a picture of him, with another person — white and, well, ghostly — superimposed over him. Mumler showed the photo around, mostly as a joke, but it somehow made its way into the possession of a spiritualist magazine. The magazine published the photo, and Mumler shrewdly realized that he had a business opportunity on his hands.

Mumler put on a good show — he claimed to channel the spirits, and said that he couldn’t do too many photos in a day because it was too taxing. People came to him from all over the country, asking him to capture them alongside the spirits of the dead.

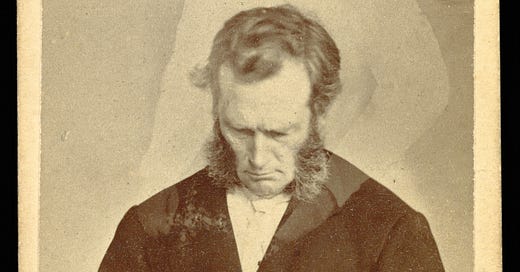

The most common versions of Mumler’s spirit photos featured a living person with a ghostly presence hovering behind or alongside them. We see a man named Bronson Murray with a woman gently touching his shoulders:

And a Mrs. Sawyer, with a ghost perhaps lowering her dead child into her arms:

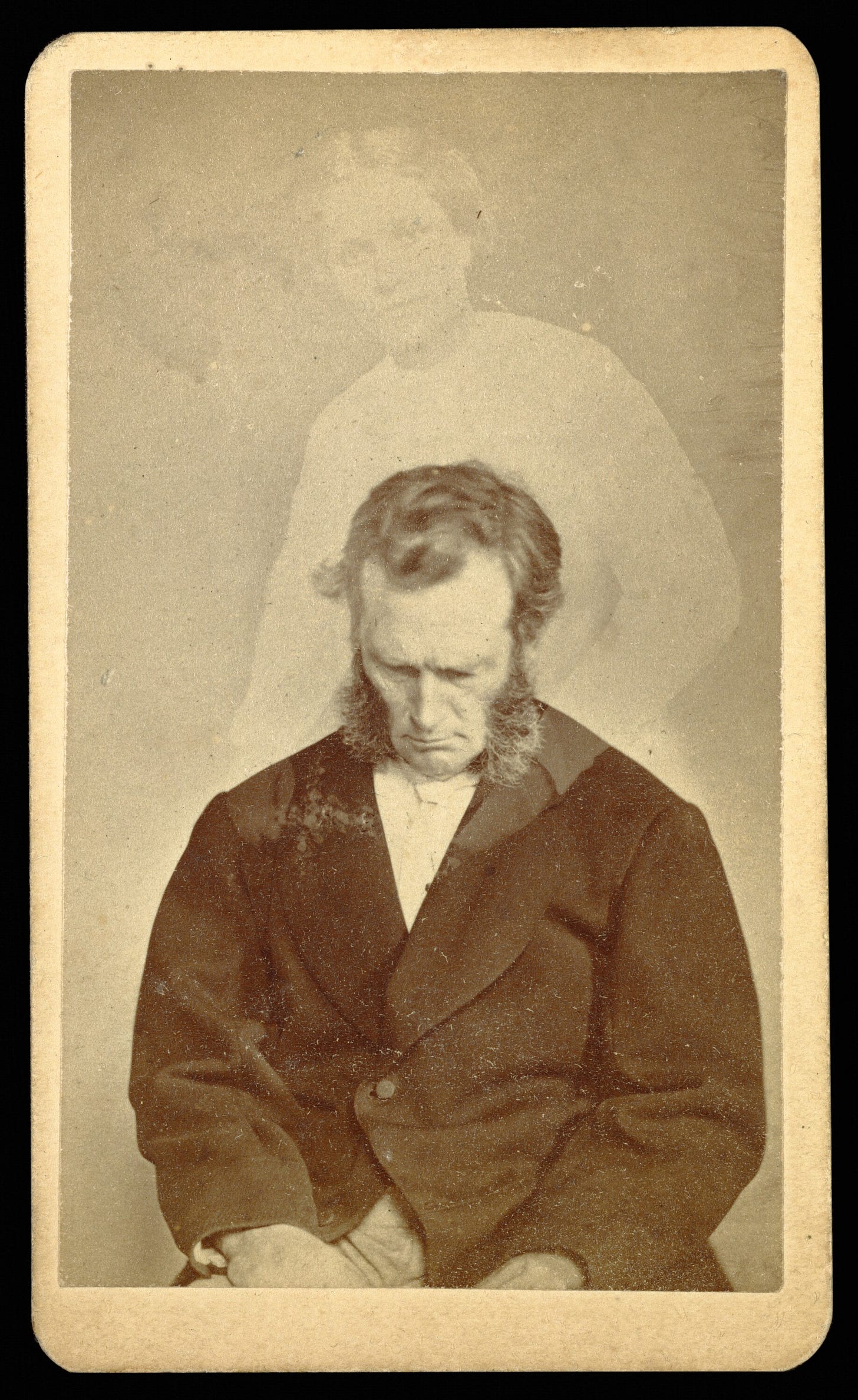

Sometimes, Mumler pretended that a photograph could summon the spirits of the dead, as in this image:

Or in this photo of the “spirit-wife” of a Mr. Tinkham:

Mumler’s pictures weren’t always very well-executed, as in this woman with “spirit arms” superimposed over her head:

Eventually, skeptics killed Mumler’s business. One of his customers realized that the “spirit” hovering behind him was a man he knew, who was very much still alive. Another man recognized his (living) wife, who had recently visited Mumler’s studio, as one of the “ghosts” in a photo. Mumler’s hucksterism was too much for even P.T. Barnum, who was disgusted by the way in which Mumler preyed on grieving people. Barnum hired a photographer to make a spirit photo of himself to show how easy it was. Mumler was sued for fraud and, though he was acquitted, his spirit photography business dried up.

One of Mumler’s last clients, after the trial, was his most famous. He photographed Mary Todd Lincoln (a long-time believer in the spirit world who had held seances in the White House) in 1869, placing her assassinated husband behind her (Mumler, for his part, claimed that he had no idea who she was when he took the picture). It was the last photo of Mary Todd Lincoln ever taken, and she apparently cherished it until she died:

William Mumler may have been the first spirit photographer, but he wasn’t the last.

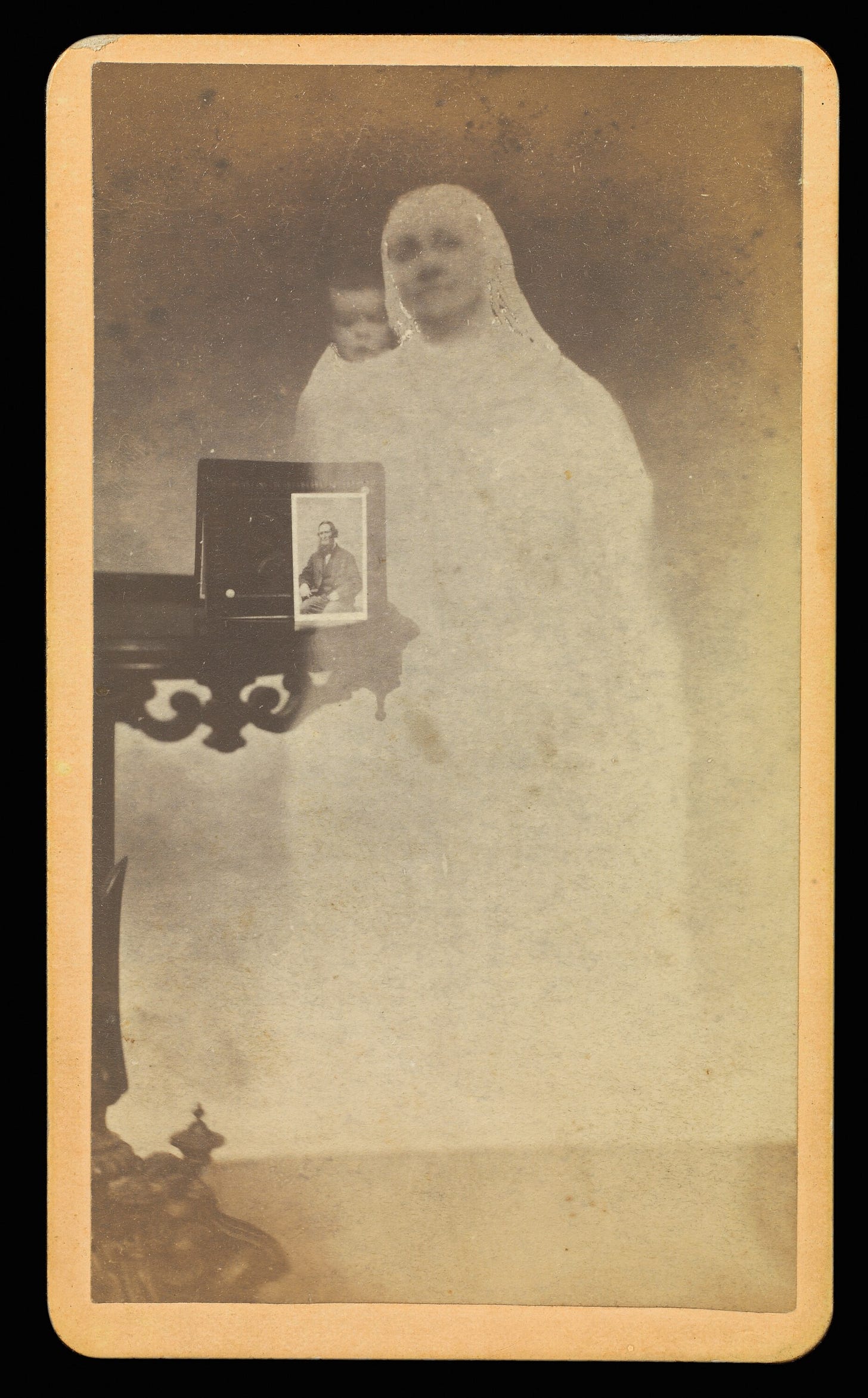

In Britain, a series of photographers started making images of supposed ghosts. Frederick Hudson of London introduced the art into London, publishing an album of spirit photographs:

A Frenchman named Edouard Buguet claimed to have taken this image of the ghost of Napoleon III in the 1880s. Buguet would later be arrested for fraud; his confession was widely published.

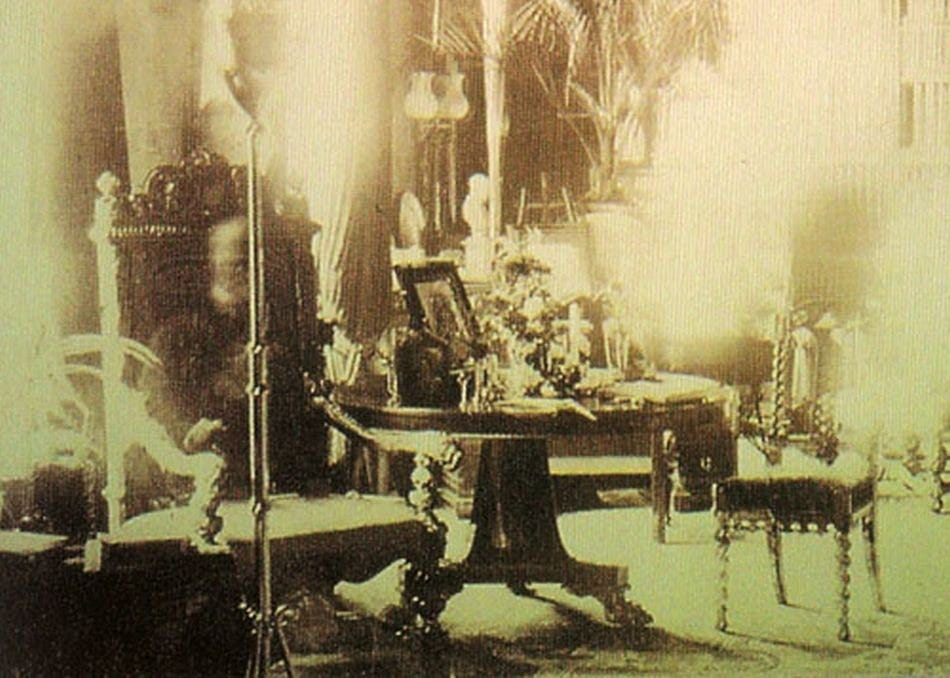

And Sybell Corbett took this infamous photo of the Combermere Abbey library, supposedly showing the recently deceased Lord Combermere (in reality, it probably shows somebody who briefly sat in the chair during the long-exposure photo process):

Despite pretty clear evidence of charlatanism in the spirit-photography game, there was still interest in photos of ghosts into the twentieth century. The last major practitioner, William Hope, from Crewe, England, was a little more sophisticated than the sloppy hucksters that preceded him. Hope invited his subjects to inspect his camera before he took the picture, and he allowed them to bring new, sealed photographic plates.

He was also closely connected to the spiritualist movement, which used his photos as proof that there was a spirit world. Hope’s photos, like the spirit photography that preceded them, duped grieving people who were eager to believe that their loved ones were out there somewhere.

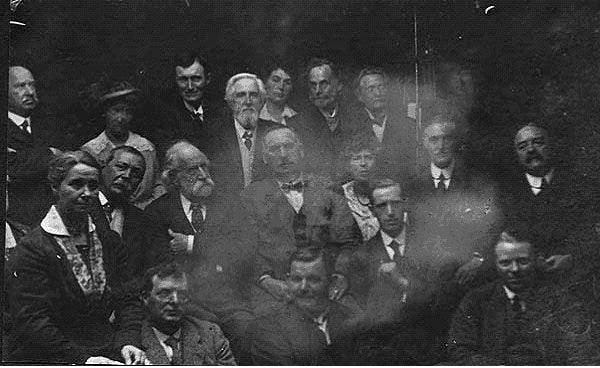

Hope’s images were, like the others, just double exposures. Here’s a “spirit photo” featuring the Crewe Circle of spiritualists, including Arthur Conan Doyle and his wife in the center of the group:

Many of the spiritualists who bought into Hope’s photos were prominent, well-educated Englishmen. In addition to Doyle, a number of famous scientists promoted Hope’s pictures as the real thing.

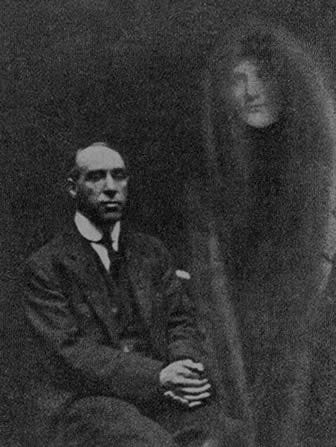

But they weren’t the real thing. Harry Price, a young magician, proved that Hope was a con man in 1922. He had Hope take this photo of him and a “spirit:”

When Price came to the studio, Hope had gone through the same procedure he did with everyone, inviting him to inspect the camera and purporting to use Price’s sealed plates. But Price had brought plates that were marked with a manufacturer’s logo, and, using his magician’s sleight-of-hand skills, had marked Hope’s plates, too. When the resulting photos didn’t show either mark, he knew that Hope had somehow switched out the plates for older ones with the “ghostly” image on them.

Price’s findings were published around the world. His proof resembled nothing quite so much as the conclusion of a Sherlock Holmes story.

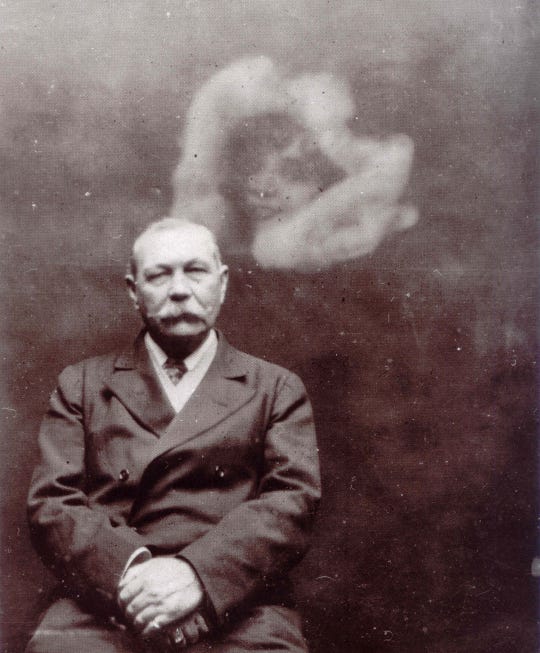

But Doyle, the creator of literature’s greatest sleuth, wouldn’t have his faith shaken so easily. He was a true believer in spirit photography, having commissioned a number of them:

The defense of spirit photography wasn’t Arthur Conan Doyle’s only public attempt to prove that the supernatural was real. Especially in the last decade of his life (he died in 1930), Doyle became one of the most prominent promoters of supernatural hoaxes. Among his spiritualist works are The Coming of the Fairies, which attempts to prove that fairies exist, and The Edge of the Unknown, which argues that Harry Houdini — who had directly told Doyle that his illusions were just that and nothing more — had supernatural powers.

I guess it’s one thing to create the world’s most rational man, and another thing to be rational in one’s own life.

This newsletter is free to all, but I count on the kindness of readers to keep it going. If you enjoyed reading this week’s edition, there are three ways to support my work:

You can subscribe as a free or paying member:

You can share the newsletter with others:

You can “buy me a coffee” by sending me a one-time or recurring payment:

Thanks for reading, and I’ll see you again next week!