When I was a kid, my family would take long summer road trips in our station wagon. In some ways, this was an experience of boredom greater than any young people today could fathom. In a situation where today’s kids might while away the hours by watching videos on seat-mounted TVs, playing games on an iPad, or scrolling through an endless feed on their phones, I had a much more limited arsenal with which to kill the hours on the way to the beach.

I could read a book, at least until carsickness took over. I could listen to the car radio, which my dad controlled and invariably played country music or AM talk radio. I could try to listen to my own music on my off-brand Walkman, but The Cure could never quite drown out the low bass of Rush Limbaugh or the sports-talk station.

Or I could look at the map.

The big Rand McNally atlas we had in the car provided hours of entertainment. I’d look at places I’d been to see if the landmarks I’d seen showed up as little red points of interest. I’d investigate places so far from my experience that they might well have been on the moon: what must Alberta be like?! I’d trace highways across the continent: can you believe that if we drove west on I-80, we’d get to Salt Lake City and then Reno and then San Francisco?

The atlas wasn’t just a way to kill time; it was a learning tool and a daydream generator.

It was also nothing special. Every family had one wedged under the seats of their car.

Now imagine living in a world in which something as mundane as the Rand McNally inset map of Greater Milwaukee represented the pinnacle of human learning. A world in which most people never traveled more than a few dozen miles from home, and in which it would take at least three days, and up to three weeks, for even the elite to travel the distance my family station wagon could cover in an hour and a half.

In those days, a map of the world would have been something wondrous, containing knowledge of societies so remote as to be the stuff of fantasy. And if that map were a true work of art, it could capture the imagination completely.

We don’t know what King Peter IV of Aragon was looking for when he commissioned a masterpiece from his royal cartographer, Abraham Cresques, in 1375. It was probably intended as a gift for the King of France; at the very least, it ended up in the collection of France’s Charles V by the end of the decade. But we know what Cresques produced: one of the greatest maps in the history of the world.

The so-called Catalan Atlas has enthralled people for centuries. It was a gateway to an inaccessible and exotic world, and today, it serves the same purpose — it’s a portal through time to a society we’ll never really be able to know.

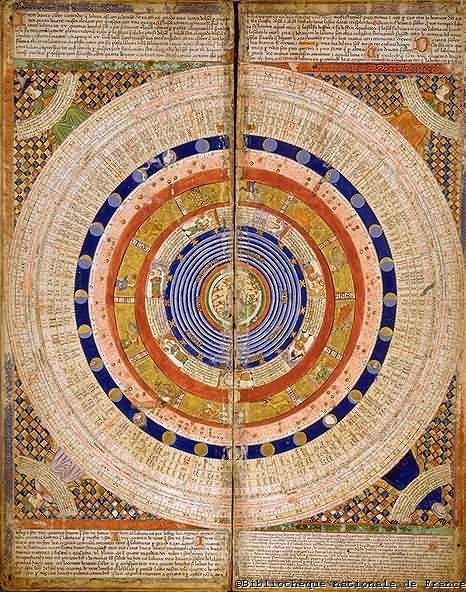

The Catalan Atlas is much more than a map. It attempts to be a compendium of knowledge about the known world. Its first few leaves contain calendars and other astronomical and scientific information. This is the first page:

These pages are too lavish to be meant as references for someone to paw through in search of the date of Easter; they’re a statement that all is in order under the royal gaze. The second sheet shows a series of circles that represent the planets and the zodiac. It’s notable that a scholar sits at the center of things rather than God:

This modern reproduction lets us see what this would have looked like a little more clearly:

But all this is just throat-clearing; the real attraction here is the map of the world itself, which you can see to the right of these introductory pages. It was meant to be laid out on a table; this means that the elements at the top of the map are “upside down” so that they’d appear right side up to people on that side of the table.

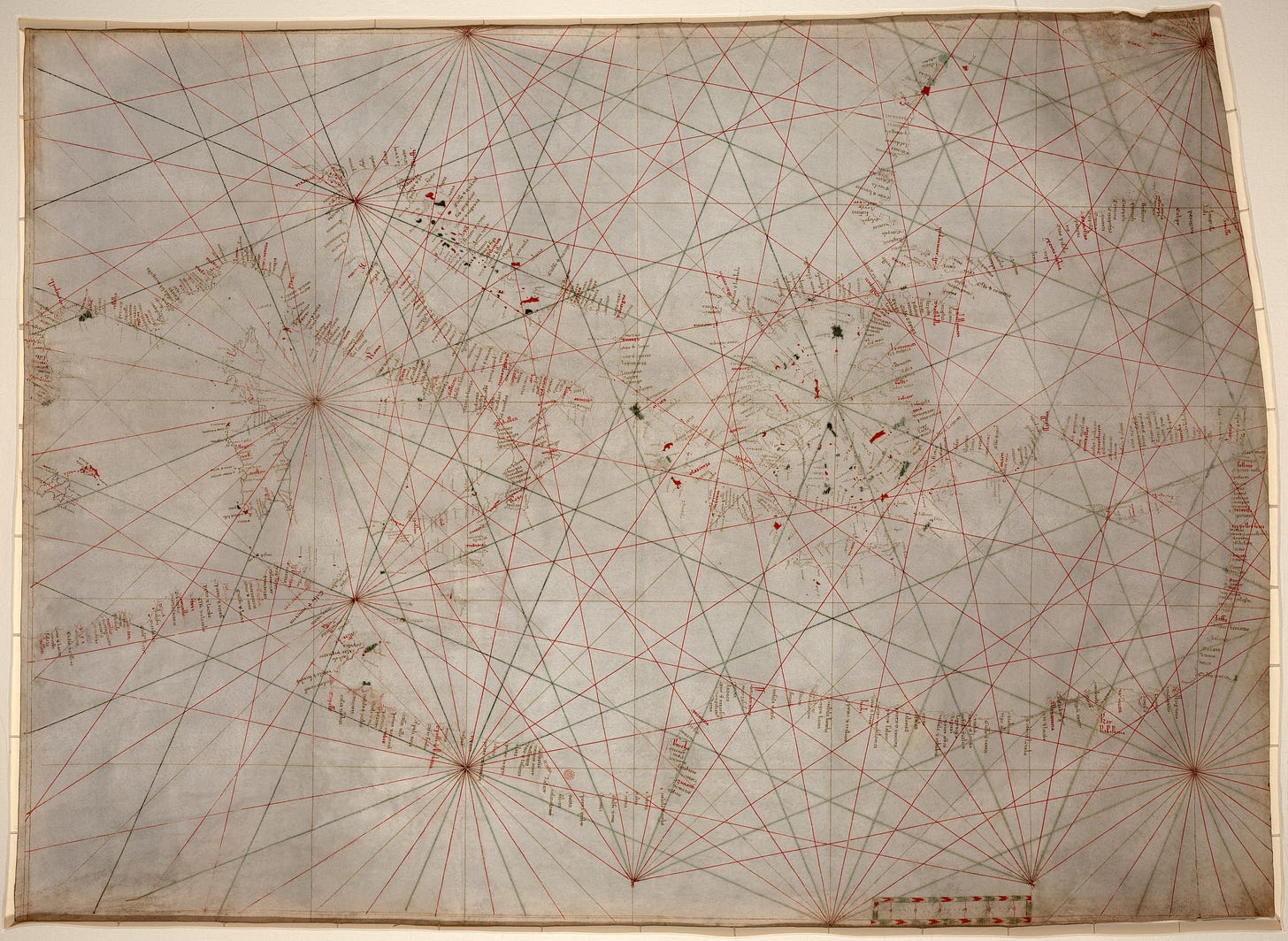

The Catalan Atlas was an attempt to combine the two types of maps that were most common in the medieval world. Navigators used the portolan, a practical nautical chart, to find distances between destinations. This one, from the early 1300s, shows the Mediterranean:

Then you had the so-called “T-and-O” map or mappa mundi, which often put Jerusalem at the center and the East (the location of the Garden of Eden) at the top of the map. These maps contained some useful geographical knowledge but also represented theological conceptions of the world (note that each continent below is associated with one of Noah’s sons: Sem, Jafeth, and Cham:

The Catalan Atlas tried to do all of the above, combining navigational information with geographical and cultural depictions of the world — or at least as accurate as a mapmaker in medieval Majorca could be.

As a result, we get a remarkable tour of the world, both as it was and as it was imagined by Abraham Cresques. Let’s go around the table, starting in Spain.

As you might imagine, Cresques’ map of Spain was spot-on. He painted his own island with the red-and-gold colors of Aragon; the map shows major Christian cities like Cordoba, the Muslim territory around Granada, and the Pyrenees Mountains to the north:

As we pan further south into Africa, we find a more fully-realized version of life there than we usually get from medieval European maps. In West Africa, we see various cities, illustrated with depictions of the people who lived there. A nomadic trader crosses the Sahara on a camel, and one of the few recognizable individuals on this map sits on his throne: Mansa Musa, the immensely wealthy king of Mali (who had died about 40 years before this map was made). The text to his right reads (this and all other inscription translations come from the very useful Cresques Project website):

This black Lord is called Musse Melly and is the sovereign of the land of the negroes of Gineva [Guinea]. This king is the richest and noblest of all these lands due to the abundance of gold that is extracted from his lands.

As we move east in Africa, we see a camel trader, a rather skinny elephant, and “the King of Organa, a Saracen that constantly battles with the Saracens of the coast and with other Arabs.”

In Egypt, Cresques uses gold to catch the eye, letting us know that “This sultan of Babylon [really Al-Fustat, or Cairo] is great and powerful amongst those of this region.” I really like the long-tailed bird that sits astride the Nile.

Arabia seems important mostly for its trade goods and connections to the Bible: “Arabia Sebba. The province that had queen Sebba [the Queen of Sheba]; now it belongs to the Arab Saracens, and in it there very good aromas, as well as myrth and frankincense. Gold, silver and precious stones are plentiful, and there you can find a bird named Phoenix.”

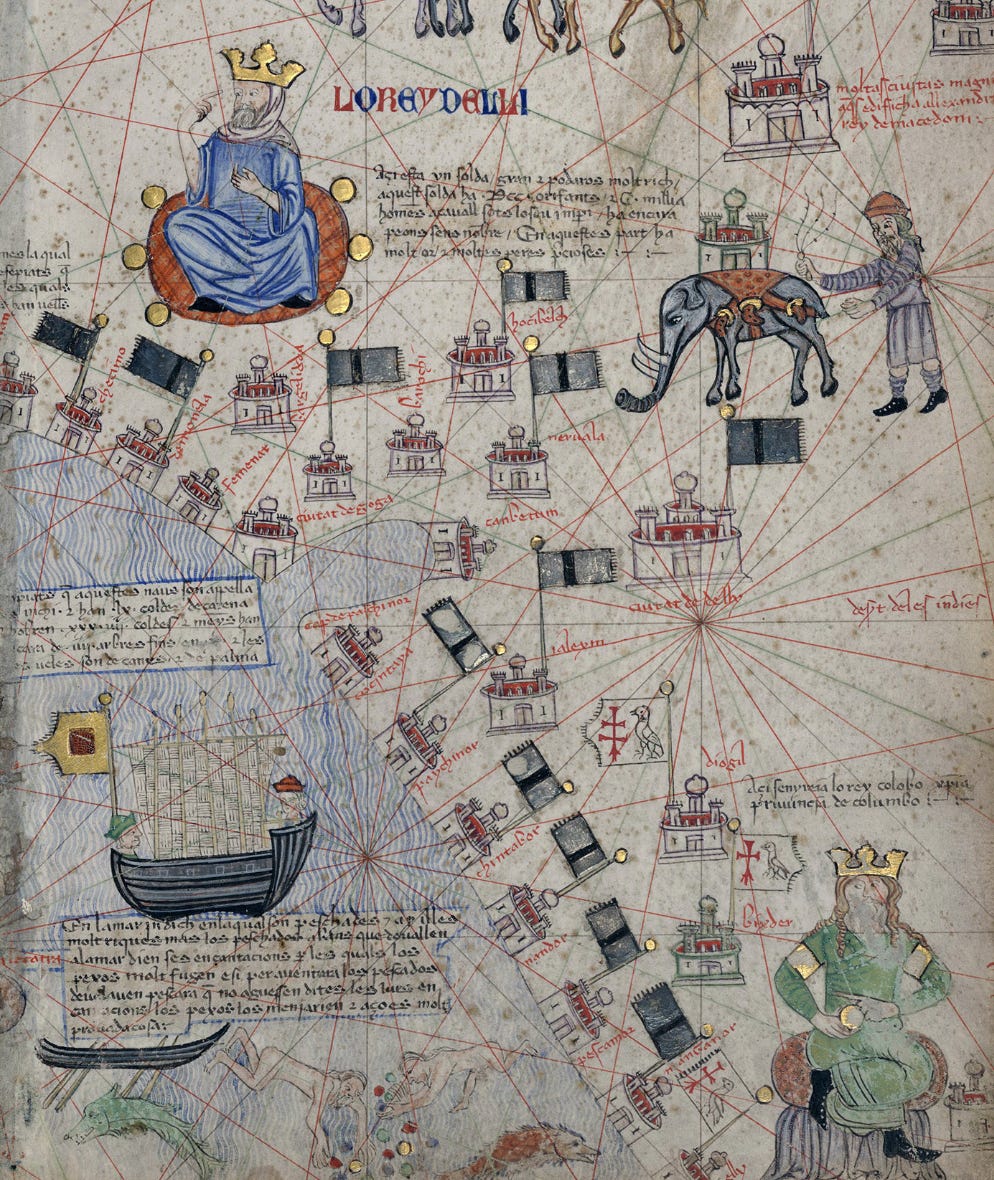

What did Medieval Spaniards know about India? They understood that it was wealthy and powerful, and that it sat at the center of the great trade routes of the Indian Ocean. The inscription tells us of a “great sultan, powerful and very rich. This sultan has seven hundred elephants, one hundred thousand cavalry soldiers under his command and even countless foot soldiers. In these regions, one can find plenty of gold and many precious stones.”

As you might imagine, the further east he goes, the more Cresques fills the map with guesswork and myth. But, in line with his general attempt to be as realistic as possible, he doesn’t fill the map with monsters, just with the legends of Asia that were known to him at the time. Some of his information probably came from the stories of Marco Polo, some came from legends about the travels of Alexander the Great,

and some came from the Bible.

There was some accurate information, mostly about trade goods. The map tells us about the island of Jana (maybe Sri Lanka) where there are “many trees of aloe, camphor, sandalwood, fine spices, galangal, nutmeg and the tree of cinnamon which spice is most desirable than any other from India.”

At the easternmost points on the map, Cresques gives us “savage” people who eat raw fish and go naked along with “the last island of Orient. The island is inhabited by people that are very different from the rest; there are burly men in some mountains of this island, twelve-cubit in height, like giants; they are very black and dim-witted; they eat white men and foreigners should they be apprehended. In this island, there are two summers and three winters and trees and herbs flower twice a year.” Note the mermaid at the bottom left!

North of that, we flip our perspective. We get Alexander the Great facing off against Satan (upside down) and the Biblical lands of Gog and Magog (at the bottom of this image):

In northern Asia, we see someone being cremated, a practice that seems to have fascinated Cresques, and an improbable tale of diamond mining from the stories associated with Alexander:

These men are chosen to pick diamonds. However, because they cannot climb the mountains where these are found, they cleverly toss pieces of meat where the precious stones lay. The stones adhere to the meat and detach [from the rocks]. Later the stones fall from the meat hoisted by the birds. Thus told it, Alexander.

There’s also an island where the falcons so beloved by Asian kings breed toward the bottom:

In central Asia, we see a caravan traversing the steppe:

And the “Sea of Serra and Bacu” (a not-very-accurately-shaped Caspian Sea):

Past the Baltic coast of eastern Europe (he seems not to have found much of interest here)…

We get Scandinavia and the British Isles. Ireland sounds pretty interesting:

In Hibernia [Ireland] there are many wonderful islands whose existence can be credible; among them, there is a small one where men never die, because when they are about to die of old age, they are transported outside the island. There are no snakes, frogs, nor poisonous spiders because the soil repels them given that this is where Lacerie Island [Cléire/Clear Island] is located. Furthermore, there are trees that attract birds like ripe figs. There is also another island where women never give birth because when they are about to give birth, they are taken outside the island as it is customary.

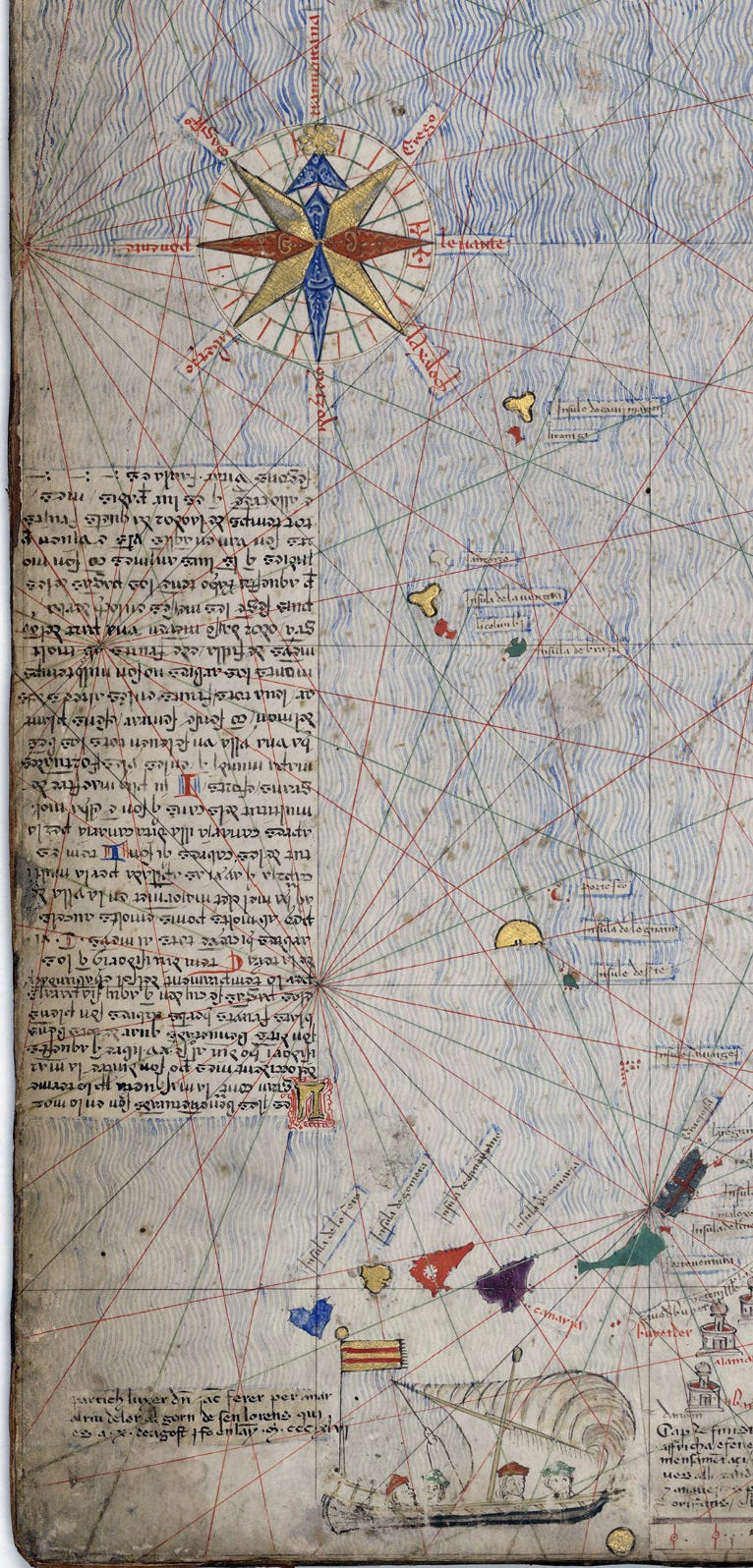

Out beyond Europe, Cresques gives us evidence that Europeans’ horizons are expanding. He shows us the Canary Islands off the coast of Africa, with an Aragonese sailing vessel setting out into the great ocean. And, significantly, he includes one of the first decorative compass roses, a useful ornament that would become an ornamental staple of maps:

Cresque’s version of the world is an intriguing combination of myth and reality, full of powerful kings and weird little guys. You’ll notice that the lines of navigation — representing the 16 directions on the compass from a particular point — stretch across every inch of the map. In 1375, it seems, Europeans were starting to stand around maps and think that it was possible to travel to these lands which had once seemed impossibly far away.

This newsletter is free to all, but I count on the kindness of readers to keep it going. If you enjoyed reading this week’s edition, there are three ways to support my work:

You can subscribe as a free or paying member:

You can share the newsletter with others:

You can “buy me a coffee” by sending me a one-time or recurring payment:

Thanks for reading, and I’ll see you again next week!

Thanks George, I got it. Mary Ellen

Brilliant! Maps have always stirred my soul. I trace my fascination with them to the National Geographic subscription that my parents maintained from the year of my birth until my dad died. There was a cabinet in our garage where my dad stored each year’s 12, always carefully tied up by string. Who needed anything else to promote an interest in the world far beyond where I lived my day to day?