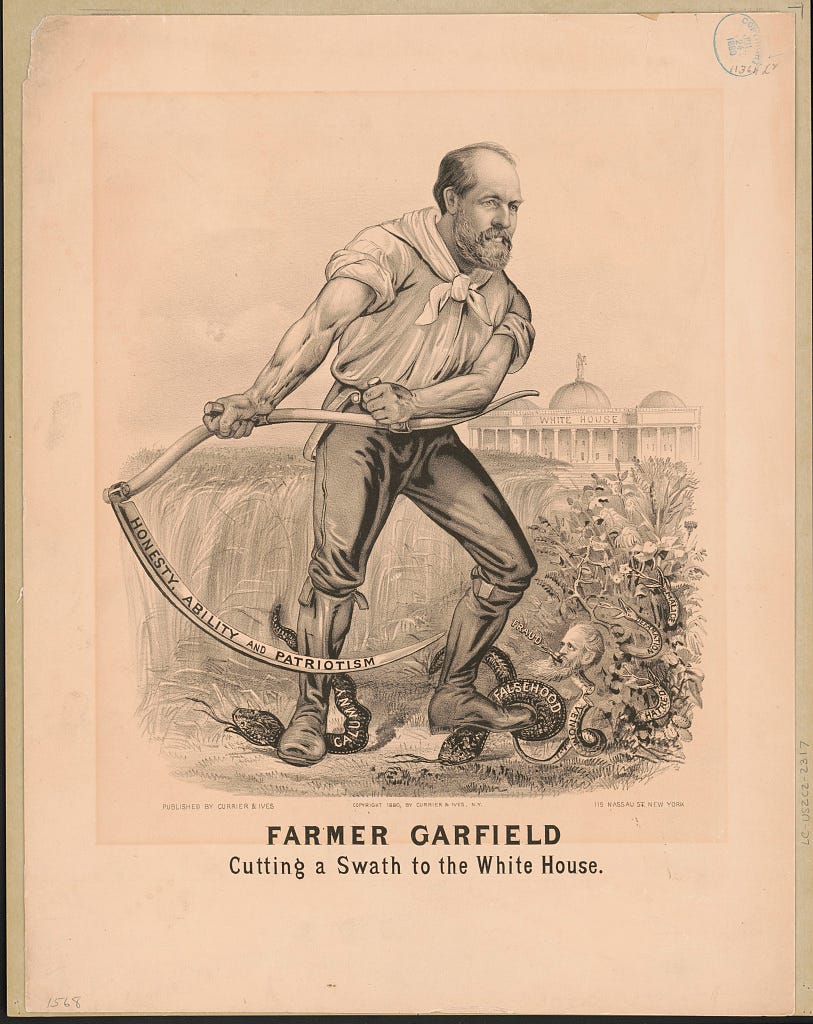

What Corruption Looks Like

Gilded Age cartoons take on machine politics

I didn’t really have a mental picture of what President James Garfield looked like, but I didn’t expect him to be jacked.

When this cartoon was produced by Currier and Ives in 1880, Garfield was almost 50. In real life, he looked like this; I suppose it’s hard to tell what kind of guns he had hidden under those sleeves.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Looking Through the Past to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.