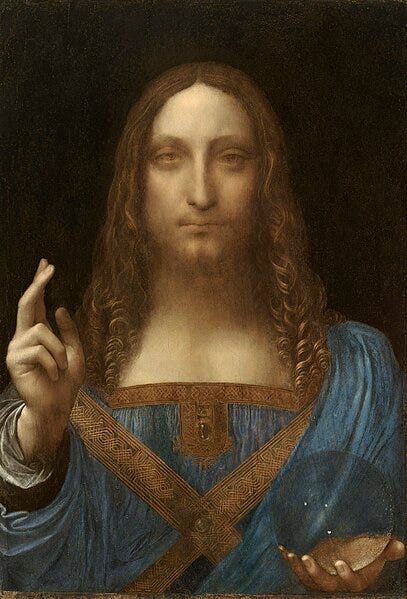

In 2017, a painting most people had never seen or heard of sold for almost half a billion dollars. Salvator Mundi, an image of Jesus likely painted by Leonardo da Vinci, was purchased by the Saudi royal family for $450 million, making it comfortably the most expensive artwork ever.

The painting’s path to promine…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Looking Through the Past to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.